Defining Rotations

Task

Consider the following possible definitions for rotation of the plane by an angle $a$ about the point $P$:

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane, then we send $Q$ to the point $R$ so that the measure of $\angle RPQ$ is $a$.

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane, then we send to $Q$ to $R$, where $|QP| = |RP|$ and the measure of $\angle RPQ$ is $a$.

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane, then we send to $Q$ to $R$, where $|QP| = |RP|$ and the measure of $\angle QPR$ is $a$.

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane and $C$ is the circle with center $P$ containing $Q$, then we send $Q$ to the point $R$ on $C$ so that the measure of $\angle QPR$ is $a.$

Which, if any, of these definitions are valid (that is, do they make sense and have the desired effect) for all points $P$ and $Q$?

IM Commentary

The goal of this task is to encourage students to be precise in their use of language when making mathematical definitions. After working on this problem, they should be prepared and encouraged to give a proper definition of a rotation by an angle $a$ about a point $P$. The rotation by an angle $a$ about $P$ maps $P$ to itself; for any point $Q \neq P$ it sends $Q$ to $R$, where $|QP| = |RP|$ and the measure of $\angle QPR$ is $a$.

Providing precise definitions for the different rigid motions of the plane is challenging. This comes in part from the fact that we have a natural visual intuition for what it means to rotate, translate, or reflect the plane. As a result, it is easy to rely on this intuition and not communicate the correct information with the definition. This task looks at some reasonable possibilities for defining rotations: each definition has at least one problem but it takes patience to exhibit cases where they fall short. Parts (c) and (d) are essentially correct and just require an additional note stating the (clear) fact that the center $P$ of rotation does not move when we apply the rotation.

Rather than asking students whether any of the definitions are valid, the teacher may prefer to tell students that none are valid and ask them determine why. Also, instead of these definitions, the teacher may wish to take proposals from (groups of) students. Although the definitions of the different transformations inevitably come early on in work with rigid motions, this task should not be done until students have some level of comfort with this material. Ideally they have already gained this in their previous courses but it is not a bad idea to postpone this discussion until later on in the course: this is because without a good stock of examples and experience with reasoning, it is difficult to identify what is good or bad with a particular definition.

Work on this task exemplifies MP6, ''Attend to Precision.'' Indeed the subtitle of this mathematical practice is ''Communicate Precisely'' which requires using language carefully and, in particular, defining concepts crisply and precisely.

Solution

-

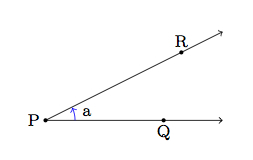

There are several problems with this definition. Most notably, it talks about ''the'' point $R$ so that $m(\angle RPQ) = a$ but there are multiple such points and so if we are not careful we end up changing the distance from $P$ to $Q$ after rotating. Here is an example of a point $R$ which satisfies this definition but $R$ is not the rotation of $Q$ about $P$ by an angle of $a$:

This definition also suffers from the flaws of the definitions in parts (b) and (c) indicated below.

-

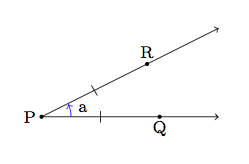

This definition captures one of the essential aspects of rotations, namely that these maps do not alter distances between points. One problem with this definition is that the rotation goes from $\overrightarrow{PQ}$ to $\overrightarrow{PR}$ and therefore it is not $\angle RPQ$ but $\angle QPR$ whose measure is $a$. In other words, the number $a$ has a sign, positive for counterclockwise and negative for clockwise. This definition ''reverses'' the sign. Below is a picture:

The second definition has an additional flaw as well as indicated in part (c).

-

This definition gets the direction of the rotation correct and the fact that it preserves distances. The only flaw here is a very subtle one: it does not tell us where to send the point $P$, the center of the rotation. Intuitively we know that $P$ does not move when we perform the rotation but this needs to be specified in the definition. In this definition, there is no angle formed when $Q = P$ and so the definition does not tell us what to do with $P$.

-

This definition comes with the same picture and has the same content as (c):

Here too, something needs to be said about what we do with the point $P$. In particular the point $P$ is sent to itself. In this case, it does make sense to talk about a circle of radius 0 with center $P$: this would just be the point $P$. The angle in question, however, would be $PPP$ and this does not make sense.

Defining Rotations

Consider the following possible definitions for rotation of the plane by an angle $a$ about the point $P$:

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane, then we send $Q$ to the point $R$ so that the measure of $\angle RPQ$ is $a$.

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane, then we send to $Q$ to $R$, where $|QP| = |RP|$ and the measure of $\angle RPQ$ is $a$.

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane, then we send to $Q$ to $R$, where $|QP| = |RP|$ and the measure of $\angle QPR$ is $a$.

- If $Q$ is a point in the plane and $C$ is the circle with center $P$ containing $Q$, then we send $Q$ to the point $R$ on $C$ so that the measure of $\angle QPR$ is $a.$

Which, if any, of these definitions are valid (that is, do they make sense and have the desired effect) for all points $P$ and $Q$?